How you weave, that’s how you dress. This is just as true today as it was over 30,000 years ago. The first evidence that we humans have always had the inclination and urge to condense, bring together and connect individual things dates back to this time. In the case of weaving, these are threads or yarns mostly made of wool, silk, flax or even living materials such as bast or plant fibers.

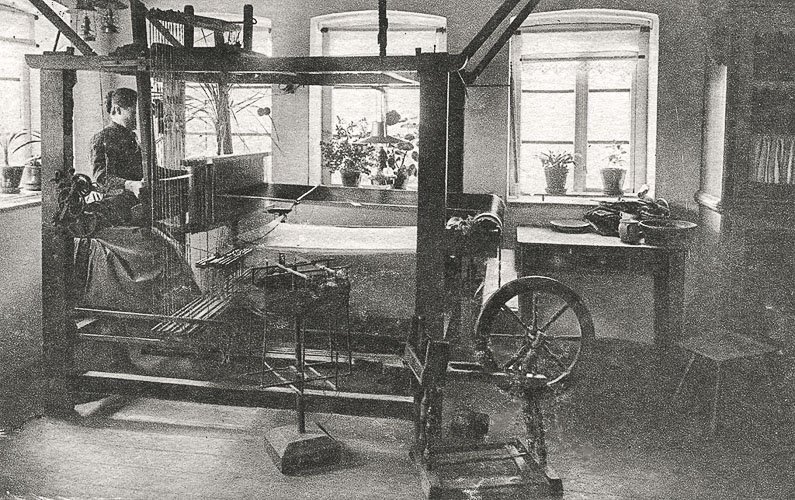

Hand loom with dobby at the Textile Center Haslach, Upper Austria – Karl Gruber, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

As part of a fabric, these filaments give up their individuality to create something common and greater at the same time: Cloths, garment, carpets or even wallpaper. Elaborately ornamented ceremonial cloaks and robes, woven fabrics as burial objects, bandages for mummies.

Weaving around the world

Even into modern times, these textiles were produced on hand looms. Just like many other crafts and their tools, weaving developed practically in parallel in many different places on earth. Depending on the resources – i.e. available raw materials – and location (i.e. whether on the water, in the countryside or in the city), people wove on a weight loom, on a horizontal loom, a high loom or a pit loom, or even on a treadle or loin loom. The threads and yarns were woven horizontally or vertically, standing or sitting.

Just as different as the origin of the fabrics were their forms, ornaments, functions and uses. What all textiles have in common is that people had to find their way step by step to the extraction and preparation of the natural material necessary for this purpose. This happened mainly through the cultivation of plants and the domestication and breeding of sheep.

Wolle vom Gotlandschaf nach der Schur und gewebt.

In this respect, the sedentariness of the people was another important prerequisite for the development of weaving. For even if, at least in Europe, weaving was initially done standing up, in order to operate a loom with heavy weights or large frames, it was necessary to have a permanent “residence”, whether in pile dwellings or in the shadow of the pyramids.

Weaving and trade

Different looms and weaving techniques allowed the production of equally different textiles. Shorter or longer, narrow or even wider fabrics were possible depending on the loom. And those who did not know how to weave large-scale or ornamental patterns imported appropriate textiles, for example from China, where silk fabrics had long been used. Weaving with different materials went from being a necessity to a commodity.

From China and the Orient, new patterns, fabrics and techniques made their way to medieval Europe, where they underwent changes, adaptations and further developments. The products of weaving became a commodity, finding their way via Byzantium and Greece to Sicily and Venice, and from there to northern and western Europe or even Russia.

Weaving as a political issue

Charlemagne had already been presented with precious silk fabrics by a delegation of the Caliph Harun ar-Raschid. His entourage, in turn, was amazed at the awning made of the finest linen under which the Arab delegation stayed.

Likewise, it was Charlemagne who decreed in his Admonitio generalis, or general decree, that women were not allowed to weave cloth, pluck wool or beat flax on Sunday, but were to go to mass. This Sunday weaving ban, however, did not apply to the king’s daughters.

The Norman king Roger II, in turn, pre-empted a war for the best minds in the weavers’ guild and unceremoniously kidnapped the best silk weavers from Corinth to his Sicilian kingdom in the 11th century, which in turn culminated in a trade war with Byzantium and Venice.

Piero del Pollaiolo, Portrait of a young lady, ca. 1465, Gemäldegalerie Berlin – Piero del Pollaiolo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Woman at a hand loom for linen in Bielefeld – Jöllenbeck around 1900

Verlag Tigges Gütersloh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Weavers’ guild

Like any other craft, weavers at some point organized themselves into a guild, also in order to share in the wealth of the cities and their rule. In Europe, the late Middle Ages was the founding period of these associations. For the more important the weavers became because of their economic importance, the more they naturally wanted to pull the strings for their own interests and income – even outside the thousands of small and medium-sized weaving workshops.

The more organized and influential the industry of weaving became, the more so-called home weaving workshops sprang up, or rather from the parlors and cellars of poor peasant houses.

For the peasants, and especially for those with little land, weaving was a bitterly needed sideline. Mostly they had to buy the yarn from their “business partners”, the factories and publishing systems, from which they then produced commissioned work and these were then bought from them in turn. Or else, a master craftsman would arrange orders for the home weavers and secure a commission from their wages.

Romantic, that is probably certain, was the house weaving rather not, but hard and poorly paid piecework in the family.

When weavers fight back

As early as 1369, there was an uprising of the weavers in Cologne that lasted for more than two years. The reason for this uprising was the will of the Cologne weavers to participate in the power of the patricians. But the aristocrats had the rebellion bloodily suppressed, confiscated the weavers’ property and banished the remaining rebels from the city.

In later centuries, weavers rose up again and again to protest their precarious working and living conditions. Too little pay, too greedy trader, cheaper production from more industrialized foreign countries, and also the triumph of automatic weaving machines at the beginning of the 19th century drove wage weavers onto the streets again and again.

Among the uprisings that have received special attention thanks to literary treatment is certainly the uprising of the Silesian weavers in 1844. Both Gerhart Hauptmann’s play “The Weavers” and Heinrich Heine’s poem “The Silesian Weavers” record the suffering, anger and ultimately the brutal suppression of the Silesian weavers’ revolt.

Carl Wilhelm Hübner, The Silesian Weavers, 1846 – Machahn 16:14, 25 October 2006 (UTC), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

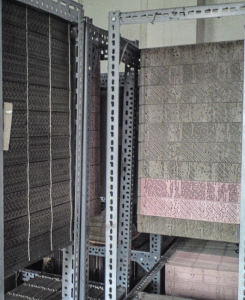

Punch card controlled loom eats up weaving art

The year 1805 heralds the end of handloom weaving – based on binary formulas, as it were. French silk weaver Joseph-Marie Jacquard invents an automatic loom based on existing technical weaving innovations, which controls thread raising and lowering practically by itself with the help of punched cardboard cards.

Thanks to control by means of endless punched cards, from now on all conceivable patterns, even of the greatest complexity and variety, can be produced quickly, cheaply and in bulk and mechanically. Thus, shortly after the end of the French Revolution, the guillotine sinks over the heads of the handloom weavers.

Just as the weaving craft is thus gradually carried to its grave, a new industrial life is born less than 100 years later thanks to control by endless punched cards. Based on Jacquard’s punch card principle, the American Herman Hollerith invented a tabulator machine for (binary) data processing in the late 1890s. Later, the computer pioneer IBM would emerge from the company he founded at that time. Mechanically processed fibers thus paved the way for what we know today as the Internet and thus also as a kind of fabric made up of billions of loose connections.

Damastweben, lochkartengesteuert

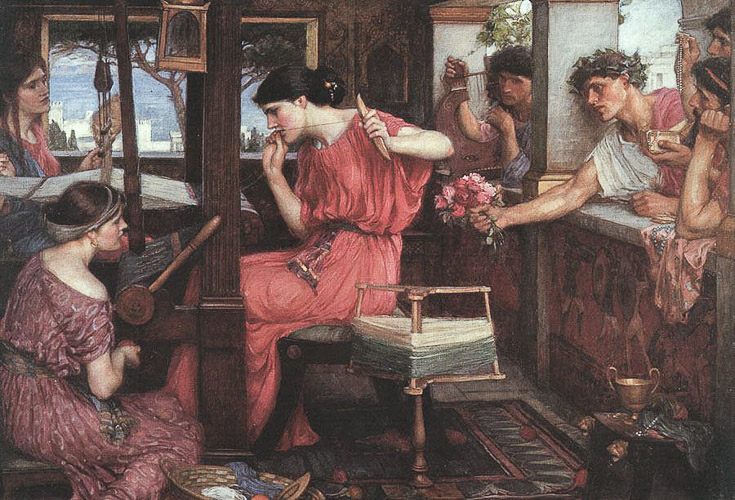

John William Waterhouse, Penelope and the Suitors, 1912, Aberdeen Art Gallery, John William Waterhouse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Woven historical fabric

The art of weaving and the bringing together of many thin threads to form a narrative thread: how could these two images not be understood as a self-evident symbiosis. For it is possible that our ancestors were already telling each other exciting stories as they wove twigs and branches into baskets, and perhaps also later, when they let the first shuttles glide through their looms.

What might they have told each other? Perhaps the story of Odysseus’ wife Penelope, who keeps her numerous suitors at bay during her heroic husband’s long absence by telling them that she is weaving a shroud for her father-in-law, only to unravel it again at night?

Or perhaps they sang the song of Hezekiah, king of Judah:

I have finished weaving my life like a weaver;

he cuts me off from the thread.

Or they listened to the story of Delilah, who desperately tried to understand how she could bind the bear-strong Samson to her. Clearly, by weaving together seven of his curls with her loom. But that is another story.