/On the emergence and decay of the elements.

We usually associate the term beauty with perfection, flawlessness and durability. We admire works of art that were created for eternity. But isn’t it imperfection what has its very own appeal? After all, life itself is based on constant change. For it is only through change that the new can emerge.

Oxidation as a productive force

A good example of this is the principle of oxidation. In this chemical process, various materials react with oxygen, thereby changing their structure. Many craft techniques use oxidation productively. For example, iron objects can be protected with a layer of rust.

When dyeing with indigo, the fabrics soaked in the vat initially appear yellowish-green. Only oxygen in the air produces the desired blue coloration.

Tea (camelia sinensis) varieties also differ with the degree of oxidation. From unfermented green tea, slightly fermented white tea to strongly fermented black tea.

If iron is treated with unfermented green tea leaves, it oxidizes, especially if it is heated together and the liquid is allowed to evaporate. An oxide layer is formed, which protects the iron if it is sealed afterwards, e.g. with oil, or if it is kept dry.

Oxidizing forged iron brooches in iron bowl – heated together with green tea leaves.

Treatment cast iron Japanese tetsubin (water kettle) with green tea to reseal the inside surface.

Oxidation and beauty

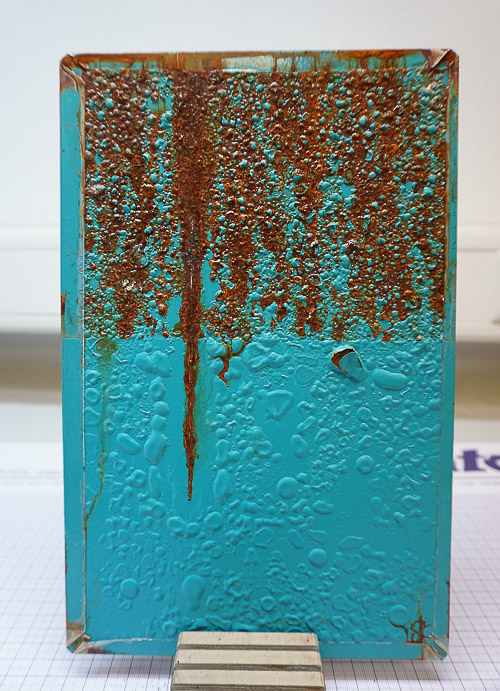

Oxidation can change the original form of objects, can dissolves boundaries and thus creates something new. Since the end of the 20th century at the latest, this effect has also been used in art. Because when metal oxidizes, an enormous variety of color shades is created. The orange-brown color of rust on old iron or the dull green of a copper roof inspire extraordinary works.

A particularly famous example of this is the “Oxidation Painting” at the Whitney Museum in New York. In 1978, Andy Warhol sprayed urine onto a two-meter-high and five-meter-long canvas coated with copper pigments. At the seventh Documenta, in 1982, the copper still had a strong sheen in many places. In the meantime, the entire surface appears much duller.

Extraordinary effects through the use of oxidizing agents

As Warhol’s artwork shows, natural rust and patina effects develop very slowly and are only possible with certain materials. The use of oxidation solutions expands the spectrum considerably. In addition to metal, rust is now conquering entirely new substrates such as paper, wood, glass, concrete or stone.

There are virtually no limits to the imagination. When artists leave puddles on the surface, cover individual parts, use salt or distilled water for dilution, or add inks and ink, surprising effects are created. Because oxidation can only be controlled to a limited extent, the attraction lies above all in experimentation.

Rust marks on a sheet metal caused by salt spray testing

MaBaOsna, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Five elements doctrine, Wuxing,

Conversion phase cycles

How oxidation relates to the Asian theory of the five elements

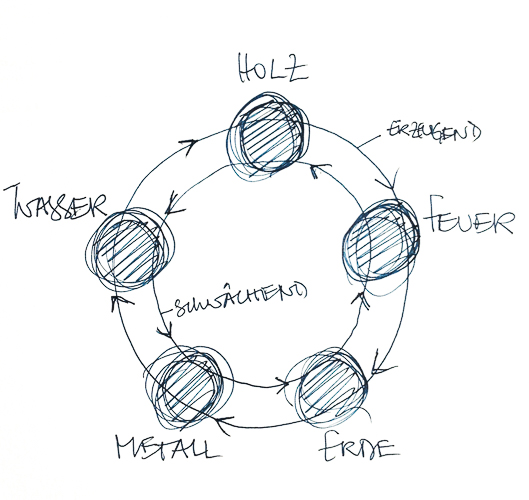

The five elements doctrine (Chinese wuxing) – or the “doctrine of the five phases of change” – traces all things back to the basic elements wood, fire, metal, water and earth and is a Daoist theory for describing nature. The elements are subject to constant change, generating and destroying each other in a perpetual cycle.

In the generation or Sheng cycle, each element nourishes the next:

-

- Wood, basis for fire

- Fire burns wood, ashes nourishes the earth

- Earth creates metal from minerals

- Metal enriches water with trace elements

- Wood needs water to grow

The opposite is the weakening cycle:

-

- Fire burns wood

- Wood absorbs water

- Water corrodes metal

- Metal pulls minerals out of the earth

- Earth suffocates fire

Oxidation, an example for the cycle of existence

The interaction of the five elements affects the most diverse areas. It determines processes in the human body as well as processes in science, society and politics. Deficiency or excess of one element disturb the whole system. Interventions therefore only make sense if they take these interrelationships into account.

Thus, even when working with oxidation, it is only possible to estimate approximately what a work of art will look like in the end. Much is beyond control. It is left to the natural course of things, which always brings forth something new from the old.

This thinking in cycles is much more archaic and older than the enlightened, linear thinking. It does not consider change as an end, but as a continuous transformation into something new. Things changed by oxidation are as much a sign of the beauty of transience as a memento for the power of change and our little influence on it.

Maple leaf, which has formed a bond with an iron shell over winter, partially gold-plated.